Columbus Premiere of Monument

On Oct. 10, the Melton Center presented the documentary film Monument (2023) with filmmaker Michael Turner. The film chronicles Turner’s first visit to a Holocaust memorial created by his grandmother Lici. She was a Hungarian Jew whose parents and sister were killed in Auschwitz. This personal documentary is a powerful and poetic story of two relatives meeting through time and space to carry their family memory forward. On this journey, Turner pieces together his family’s stories through photos and letters.

Turner’s grandmother did not talk much about her experiences, yet she traveled back to Sáravar, the village where she grew up. There was not a trace of what happened there — no markers or memorials. She decided to put up a monument so that the people of the village, her children and grandchildren would never forget what happened to the Jews there during World War II. “It felt momentous being in a place where my family lived. What made it special was knowing my family was once there. For a little while, the past came up to us,” said Turner. The monument symbolizes a headstone and a casket. His grandmother said in the film, “This is the funeral for everybody.”

Turner joined Melton Center Director Hannah Kosstrin for a post-show discussion and answered questions from the audience.

Superman's "Jewish Origins" and other thoughts on Jews and Comics

On Oct. 25, the Melton Center welcomed Samantha Baskind, Distinguished Professor of Art History from Cleveland State University. Professor Baskind discussed the Jewish origins of superhero comics such as Superman, Batman and others. Many Jews helped build the comics industry from the ground up. Before the 1930’s, she explained, there were comic strips in newspapers and other periodicals, where young Jewish comic book writers and artists had a chance to break into a new medium because at that time Jews were not getting positions at advertising agencies.

Superman has an Ohio connection as well as a Jewish one. The comic was created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster of Cleveland, who were friends in high school when they created comics. They worked out Superman’s history and origins, which began the adventure of the greatest superhero of all time. Some commentators believe Superman is Jewish: He comes to a strange land as an alien, which reflects many Jewish immigrants’ experiences in the U.S. He is taken in by a couple and his purpose is to create good in the world.

Comics were traded by GIs during the war and read by Americans at the time. Other comic book makers countered fascism in their work. While Superman comics incorporated World War II, the comics weren’t about the war; instead, the cover images of comic books depicted superheroes fighting the Nazis. One cover featured Captain America (1941–1943) with sidekick Bucky punching Adolf Hitler. The “World’s Finest Comics” show military servicemen with Superman with his arm around a soldier, and Batman and Robin shaking hands with a serviceman. Professor Baskind also discussed the graphic novel Maus to show the extent of Jewish contributions to comics and graphic novels.

Professor Baskind’s programs were part of the Thomas and Diann Mann Symposium series and were co-sponsored by the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library at Ohio State.

New Research in Jewish Studies

On Oct. 29, five of our Jewish studies faculty members presented excerpts from their current research projects and discussed new directions for research in Jewish studies. The program was held at the JCC.

Ori Yehudai, Associate Professor of History and the Saul and Sonia Schottenstein Chair in Israel Studies and Associate Professor, History

Professor Yehudai presented research on Palestinian terrorist attacks in Israel in the 1970s. He focused on public reactions and discourse following the attacks both in Israel and in the American Jewish community. This relates to relevant broader themes in Jewish studies, including the relations between Israel and American Jews, Ashkenazi-Mizrahi relations in Israel (he discussed how the ethnic Jewish conflict was related to the conflict with the Palestinians), and Holocaust memory (comparisons were made between Palestinian violence and Nazism).

Lúcia Costigan, Professor, Spanish and Portuguese

Professor Costigan’s presentation focused onEl Brasil Restituído, a play written in 1625 by the famous Lope de Vega depicting the recovery of the city of Bahía, the capital of Brazil that had been invaded by the Dutch in 1624. To convince the Spanish people of their superiority over the Dutch, and to find an excuse for the invasion of Bahía, Lope de Vega creates a plot that depicts the Sephardic population who lived in Brazil as traitors who enabled the Dutch to invade Bahía, the capital of Brazil in the 17th century. When searching literary and historic documents written in other parts of Europe at the time, one finds no evidence of the role played by descendants of Jews in the invasion of Bahía. Therefore, we conclude that Lope de Vega’s play exhibits a strong antisemitic feeling that permeated 17th century Spanish Baroque culture. Unfortunately, antisemitism and other types of prejudices are still present in our societies and can be seen in moments of crisis such as the one we are experiencing today.

Naomi Brenner, Associate Professor, Modern Hebrew and Yiddish Literature and Culture, Near Eastern and South Asian Languages and Cultures

Professor Brenner discussed a 1946 copyright lawsuit in British Mandate Palestine in which a Yiddish journalist accused a popular Hebrew publisher of plagiarizing the popular Yiddish novel Sabine. She explained how this case, which featured witnesses reading excerpts from controversial popular novels, gives insight into long-forgotten popular fiction and challenges assumptions we often make about originality and literary innovation. She also showed how this controversy represents the shifting relationship between the Jewish community in British Mandate Palestine and Eastern Europe in years immediately after the Holocaust.

Robin Judd Professor, History

Professor Judd discussed the stories of two women from Frankfurt, Germany with diverging experiences during the Holocaust to address the question of insiders and outsiders within a global perspective on Jewish history. Their stories of incarceration and liberation raised questions concerning Jewish identity and the nature of Jewish organizations in the postwar period. Moreover, the women’s migration across Europe and the networks on which they relied introduced new ways of understanding how individual Jews could become touchpoints during the ebbs and flows of migration and immobility during and after the Holocaust.

Hannah Kosstrin, Associate Professor, Dance

Professor Kosstrin discussed material from her book project Kinesthetic Peoplehood: Jewish Diasporic Dance Migrations. The book is about how people participate in the Jewish diaspora through dance practices. By focusing on the ways in which Israeli choreographers’ work circulated between Israel and the U.S. between the Cold War and COVID-19, the book also tells us how Americans understood Israel and a Jewish imaginary through the dance that they saw. She gave as example the choreography of Margalit Oved and Barak Marshall, in which Adenite hand gestures from southern Yemen demonstrate Jewish dance migrations from South Asia through Yemen to Israel and the United States during the 20th century. Dr. Kosstrin showed how Oved and Marshall repurposed and recontextualized these gestures through contemporary dance conventions toward the ends of Mizrahi feminism and self-determination.

Humor and Laughter in Religion Symposium

On Feb. 9, 2024, the Center for the Study of Religion and the Melton Center presented a seminar on humor and laughter in religion to examine what humor reveals about how communities negotiate boundaries of identity.

Professor Isaac Weiner, director of the Center for the Study of Religion, introduced the program. He said the Center for the Study of Religion aims to make space for discussions on religion and is committed to the idea that cross-cultural comparative approaches will deepen our insights and understandings of the phenomena that we study.

Four scholars discussed the importance of studying religious humor and what we gain by examining the topic comparatively and cross-culturally.

Jennifer Caplan, associate professor and chair of Jewish studies at the University of Cincinnati, is an expert on American religion and popular culture engagement. She recently published Funny, You Don’t Look Funny: Judaism in Humor from the Silent Generation to the Millennials (Wayne State University Press, 2023).

In her talk “What’s Jewish about Jewish Humor?” Professor Caplan discussed Jews and humor. She said there is not a singular relationship between Jews and humor, but rather that humor, especially Jewish humor, is generally localized. Existing literature on Jews and humor is an attempt to stitch together a far-reaching view of that relationship. Many books focus on the reason why Jews are funny, she explained, because there are examples of humor in the Bible, while others say it is not necessarily the textual traditions but a defense mechanism for the struggles and tragedies Jews have endured. Professor Caplan’s talk touched upon humor and its relationship to “cultural Judaism,” as well as the place of humor within Jewish social practices in the United States.

Samah Choudhury, assistant professor in the Department of Philosophy and Religion at Ithaca College, teaches courses on religion, race, pop culture and Islam. Her first book, American Muslim Humor and the Politics of Secularity, focuses on stand-up comedy and examines how Muslims have articulated themselves through stand-up comedy in the U.S.

In “Thinking about Religion and Race by Taking Humor Seriously,” Professor Choudhury focused on Muslim humor through the medium of standup comedy. She discussed how standup is a highly staged and embodied genre that reveals how Islam finds recognition (and becomes obscured) through discourses of race, gender, affect and American secularism. The most meaningful humor, she said, re-orients us around our common humanity. Professor Choudhury’s talk touched upon the ways that humor reveals perceived relationships between Islam and modernity, arguing that religion is an embodied experience that needs to be understood through the lens of mobility and migration.

Hannibal Hamlin, professor of English and associate director for the Center for the Study of Religion at Ohio State, is an expert on early modern English literature.

In his talk “The Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost walk into a bar…Does Christianity Have a Sense of Humor?” Professor Hamlin discussed humor in Christianity. He explained that while there are jokes about Christians and about Christianity, there is not a tradition of Christian jokes in the same way as we speak of Jewish humor. Nowhere in the Christian Bible does Jesus laugh, he noted, but the mention of laughter in the Gospels involves mocking or laughing to scorn the object of derision. Professor Hamlin referenced three dominant theories for laughter: the superiority theory, the incongruity theory and the relief theory, and explained the distinction in the Christian Bible between rejoicing with joy versus laughter.

Melissa Ann-Marie Curley, associate professor in the Department of Comparative Studies at Ohio State, is an expert on Japanese religion. She wrote Pure Land Real World: Modern Buddhism, Japanese Leftists and the Utopian Imagination (University of Hawai‘i Press, 2017).

Professor Curley premised her talk “Rain-Making and Piss-Taking: Bawdy Humor in a Few Buddhist Stories” by saying that Buddhist tradition itself is consciously not funny, and that a laughing body is a body out of control. Her examples from 17th-century Japan highlighted the urban/rural divide as well as polemical conversations about the bawdy through laughter. One can think more broadly about the kinds of laughter that can be provoked ritually in religious settings, she asserted, and what those kinds of laughter and the ways they are negotiated reveal to us about how well and to what degree religious traditions tolerate and manage being out of control.

Disordering Mysticism, Organology, and Restitution: The Ruptured Afterlives of North African Torah Scrolls

On March 4, Professor Ilana Webster-Kogen, the Joe Loss Reader in Jewish Music at SOAS University of London and a visiting associate professor at Yale University, gave a talk about how Jews of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya scattered across the Mediterranean basin, carrying with them their Torah scrolls as key objects of ritual and memory that facilitate communal worship when congregations chant from them. Her presentation considered the practice of collecting Torah scrolls from North Africa, describing the synagogues in France that use them, the synagogues in North America that “look after” them, and the non-Jewish institutions, including Arab states, that collect and display them as part of a national patrimony or religious ideology.

Professor Webster-Kogen argued that the practice of collecting Torah scrolls challenges the boundaries both of organology (what an instrument is) and heritage (the objective of restitution). Professor Webster-Kogen explained that the Torah scroll is a key conduit through which communal music-making takes place in the synagogue. In diasporic surroundings, North African scrolls are venerated, chanted from and collected by uprooted North African Jewish communities in France, but also by synagogues in the United States that have adopted the scrolls, and museums that perceive themselves to be the guardians of a lost culture.

The program was co-sponsored by the Melton Center and Ohio State’s School of Music.

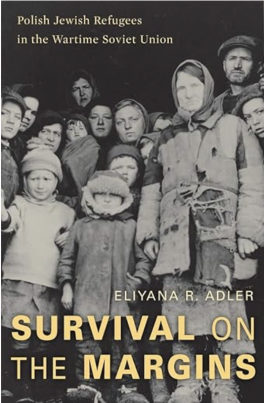

Survival on the Margins: Polish Jewish Refugees in the Wartime Soviet Union

On March 19, Eliyana Adler, associate professor of history and Jewish Studies at Pennsylvania State University, gave a lecture based on her book, Survival on the Margins: Polish Jewish Refugees in the Wartime Soviet Union (Harvard University Press, 2020) about the forgotten story of 200,000 Polish Jews who escaped the Holocaust from 1940 to 1946. Professor Adler’s talk explored how focusing on this group helps us to understand the vast scope of the Holocaust as well as the difficult plight of refugees. They were stranded in remote corners of the USSR and experienced a lack of basic necessities, and their return to Poland was traumatic because of the devastation after the war. A recording of her presentation is on our website at go.osu.edu/melton-center-past-program-recordings.